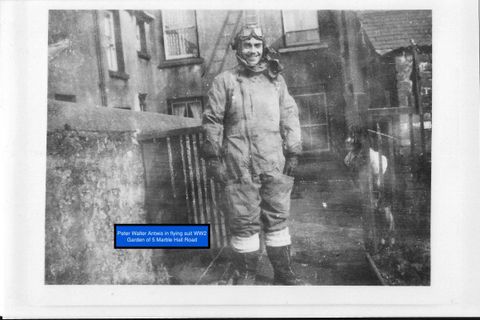

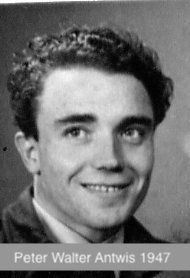

Peter Walter Antwis RAF Lancaster Bomber Navigator- World War 2

First instalment of an account by Mark Antwis

12 Aug 1944.

Dad's Lancaster has just taken off from Skellingthorne in Lincolnshire with a full load of 7 tons of high-explosive Tallboys on their fateful mission unaware of what awaits them.

Turning to head across the south coast of England where they pick up Mosquito fighter escort, with the intention of continuing down the Atlantic coast towards the Bay of Biscay. Here they will lose fighter escort and fly south east inland to the south of Bordeaux then turn north east to approach the target from the south west. Dad is working intently to ensure all the turning points are perfect and Joe has all the bearings and altitudes he needs to cross the target exactly.

Approximately 18:45.

Dad's Lancaster is approaching the target. The bomb-bay doors are opened in readiness. The bomb aimer takes his position lying prone in the nose watching through the sight to instruct the pilot. Dad can see puffs of black smoke ahead at the same height as the aircraft as shells explode, and knows the gunners below have got their range. Pieces of flak and shrapnel clatter against the fuselage and the aircraft starts to buck from the explosions around. Suddenly there is a loud bang and explosion as a chunk of angry metal passes through the cockpit, through the bulkhead in front of Dad's navigation desk, bursting his parachute sitting on the floor, and exits out through the fuselage, smashing the inboard port engine. There is an overwhelming smell of burning as a starboard engine catches fire, and glycol streams from the port engine into Dad's office. The aircraft is pitching and yawing violently as the elevators and rudder, uncontrollable due to hydraulic system damage, flap around. Joe is fighting to control the plane and has both feet against the column to keep the aircraft level. He manages to bank the plane so they swing away from the target but they are unable to release the bombs. They are now flying directly up the River Gironde back towards the Atlantic. Joe asks Dad and Freddie to see if they can release the bombs manually in the belief that if they can get rid of the seven tons of weight they might be able to limp the aircraft back to England. The fire in the starboard engine has gone out but it is now screaming uncontrollably, making verbal communication impossible and Joe's task of flying even more difficult. Dad and Freddie climb into the open bomb-bay and Dad holds Freddie by his parachute straps while he leans over and attempts to release the bombs but to no avail. The mechanism is jammed. Meanwhile the mid-upper gunner has crawled down the fuselage to the very back of the aircraft. The rear gunner is trapped helpless, unable to swing the turret around in order to get out. His mate works the manual release until the turret has turned sufficiently to open the doors and drag the rear gunner out. As they make the long journey crawling back along the twisting and bucking aircraft Joe shouts the order to abandon the plane. They are losing height and Joe knows they are stricken.

As Dad plummets out of the plane and sees his chute open everything is suddenly silent after the mayhem inside the plane and he can feel the cool summer evening air on his chest burns. He looks down to see the River Gironde coming upwards towards him.

As Dad drifted slowly down he could see he was moving closer to the shore at a remote spot in the estuary into the Atlantic. The stricken Lanc was in its final death throes. It was about a mile away, turned and headed back towards him then its nose came up, rolled onto its side and plunged into the forest, exploding as it hit the ground, the seven tons of high-explosive and hundreds of gallons of fuel sending a black plume of debris and smoke high into the air.

Freddie had recently gone whistling past him and then opened his chute and the others had bailed before him so he knew only Joe was on the aircraft. Dad saw no other chute and resigned himself to Joe having gone down with the plane.

Dad managed to manouevre his chute so he would land on a sandy strip between the beach and the forest. At that moment he heard the whistle of bullets pinging past him and realised he was being shot at from the ground. He could see emplacements of big anti-naval guns on the coast - the guards must have been alerted by the noise of the Lanc stuttering up the river and exploding in the forest. Dad knew Hitler had recently ordered that parachuting airmen were to be fired upon in contravention of the Geneva Convention.

Dad landed heavily but the soft sand broke his fall. He quickly realised he had landed in a rabbit warren and buried his chute in one of the holes.

As he made a run for the trees nearby he was shot at by a German some distance away who shouted at Dad to stop. Dad no doubt responded in the negative(!!) and kept moving then to his horror saw a sign reading to the effect he was in a minefield. Dad stopped. The guard gestured for Dad to come to him. Dad sat down and refused, at which point more shots were fired over his head. At this point a German officer arrived who spoke some English and told Dad in no uncertain terms he would be shot if he didnt come out. Dad successfully left the minefield (or I wouldn't be writing this) and was now a prisoner of war. For the time being......

1944, August 14, the Gironde:

Dad spent last night, his first night as a prisoner of war, locked in a building near the beach. (I found this building near the gun emplacements by cross-referencing the various accounts and crashing through overgrown land marked as 'Out of Bounds, Military Area'. I will post the photos later).

During last night the rest of the crew, except the pilot Joe, had been captured and locked in the German soldiers' quarters. The bomb aimer, Bill Gray, had a chunk of perspex in his eyelid from where his canopy had blown apart when he was lying in the plane's nose guiding the pilot over the target. The flight engineer, Pat Hart, held Bill's head while Dad extracted the offending perpex and dreseed him with a bandage given them by one of the guards.

The crew hundled together to discuss an escape. No one knew what had happened to Joe so it was decided to keep quiet in case he had got out and was on the run. Their belief was that he was dead.

For 50 years Dad believed he had left it too late to bail out. Had he sacrificed his life to make sure the crew got out? In the early 1990's the marvel of the internet and dogged research by Rosemary and Dad revealed Joe was indeed alive and well, living back in Australia and still flying!

In 1993, almost 50 years after their ordeal, a reunion of the three still-living crew of Lancaster VND - Dad Freddie and Joe - took place at a quiet airfield in Lincolnshire where it had all begun almost half a century before.

Joe was indeed on the run in the Forest de la Coubre close to where the Lanc had come down. He had baled out when the aircraft was so low there was barely enough time for his chute to open. The moment he had let go of the controls the nose had come up and the aircraft had begun to stall. While Dad was drifting downwards watching the nose rise and the plane drop from the sky he was unaware Joe had made his desparate scramble from the pilot's seat to the escape hatch and fallen out moments before the Lanc rolled into its side.

Joe was indeed on the run in the forest, moving by night and hiding up by day.

This afternoon in the barracks, Dad's concern was that the Germans would shoot them - the allies were advancing through Normandy and the last thing their captors needed was six airmen causing them problems when they could be soon fighting for their own survival. Dad also was aware the German sargeant was upset that the exploding Lanc had taken out some of their gun emplacements. Before the crew had a chance to hatch a plan they were shouted at and pushed and shoved by about a dozen Wermacht soldiers into the back of a truck which proceeded to head at high speed off down a country road.

At around this time, 15:00, they arrived at a small town which they discovered from one of the guards was Cognac.

They were led into a medieval fortress looking building which turned out to be the town jail. Several flights of iron stairs led Dad and the rest into a dark, stinking dormitory with buckets for toilets and mattresses on bed steads but no blankets. As darkness enveloped the damp room rats scurried around. Dad's burns were sticky and stinging under his flying jacket. What would tomorrow bring? When could they seize an opportunity to escape?

August 17th 1944:

Yesterday dad and the crew were loaded onto a truck. Spent hours crawling along packed country lanes, in the belief they were on their way to Germany. A British fighter bomber attacked, strafing the road and the truck no doubt unaware of its contents. They all dived for cover in a ditch and emerged unharmed. Dad realised they were heading roughly south and not to Germany, causing more concern they were going to be disposed of.

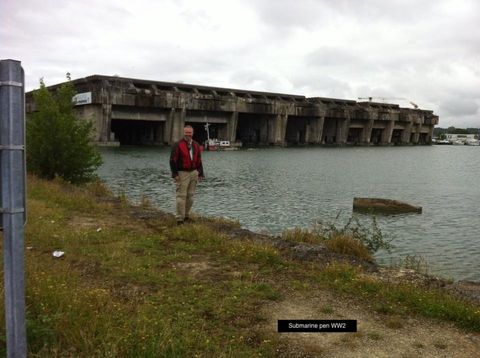

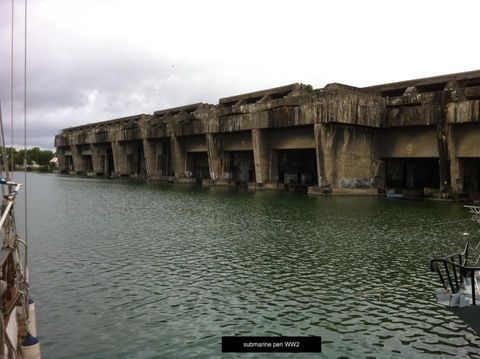

Eventually, by late afternoon they arrived at a town with heavy bomb damage. They had been taken back to Bordeaux where the submarine pens were that they had attacked 4 days before! They were incarcerated in Bordeaux prison. One can only surmise that the advancing allies had closed off any possible route to Germany and the Germans had decided to take the airmen south.

Today, they asked for medical treatment for their wounds but were refused. They were joined in their cell by ten crewmen of an American Flying Fortress. They were all in civilian clothes - they had been picked up by the Maquis and handed over to the Resistance and were on their way down the escape line to Spain. The last part of their journey from Bordeaux to the Pyrenees was to be by car. They were told to be in a certain street at a certain time. The ten of them reached the car, got in and the driver drove them to the Gestapo Headquarters - the driver was a collaborator!

There followed an interrogation of Dad and the crew by the Gestapo. The following is taken from Bill Gray's account: Each airman was interviewed separately. Dad was second into the room. The Gestapo officer wore an immaculate cream-coloured uniform. He bore a Knight-Grand Cross on his collar under his chin and an Iron Cross and other decorations on his chest, one of which (so they were told by a guard later) was for service at the Eastern Front and Stalingrad. He was tall and blonde. He spoke no English but good French so he had an interpreter who could speak English and German, very complicated!

Many questions were asked and when only name, rank and serial number were provided the officer became angry and smashed his cane down on the desk. ...he got no information. All the airmen emerged unscathed from the ordeal.

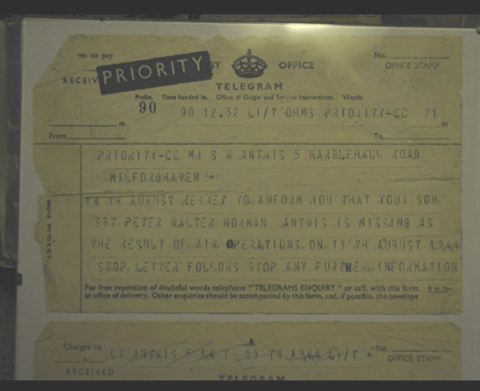

Three days earlier, on 14th August, in an ordinary house in Marble Hall Road in the town of Milford Haven in Wales, Dad’s parents received a knock at the door. The telegram (in the photo below) that every parent must have dreaded was thrust into his mother’s hand.

If you are in the area of Royan/ Point de la Coubre at the mouth of the Gironde at any time here are two maps showing the beach where Dad landed. The bottom photo is of the beach itself. Visible still are the posts and barbed wire described in great detail in Bill Gray's account. Next photo is one of the big naval guns behind the beach. The last two photos are of the barracks where they were incarcerated on the first night, now derelict in the woods behind the guns, the second of these shows the inside of the room where they were held - Freddie describes the room with a small window in the roof.

Somewhere in the 8000 hectares of forest behind the beach lies the remains of Lancaster VN-D

Just re-reading the pilot's account. If you are ever afraid or panicking or thinking something is too difficult remember the following extract from Joe's recollection of the final hour of Lancaster VN-D told in the level of detail you would expect from a very young man with hundreds of hours flying heavy bombers and the flat-line outward calmness that goes with the territory:

'Immediately obvious was severe damage to the instrument panel including the gyro instruments, a hole in the windscreen through which the wind was whistling, a hole in the fuselage just behind the pilot and the side window broken, heavy pressure on the controls, the plane trying to climb and the starboard engine losing glycol. I tried to adjust the elevator trim to take the pressure off the controls. The wheel turned more easily than it should because the chain had detached, so I was stuck with the high pressure. The engineer was trying to sort out what we had left in the way of throttle and pitch control and the bomb aimer was continuing with the bombing run although he had a piece of perspex through one eyelid. We were hit again. The pitch and throttle was mosty gone, the instrument panel out of action including the gyro compass and artificial horizon. Wind was whistling through the cockpit. The starboard inner engine was losing glycol, the port inner losing oil and both port engines had gone into fine pitch and would not come to cruising revs. Soon, the starboard inner caught fire so the engineer feathered the engine and activated the extinguisher but the engine continued to mill. The Navigator (Dad) reported there was a hole in the floor and roof between his chair and table. If he had been leaning forward at the time there would have been a hole in him also. The upper gunner said in his quiet way there was a large hole in his turret and the end of the starboard wing was a mess. The rear gunner reported no turret control and severe damage to the starboard rudder and the starboard elevator.'

The gunner was now trapped in his turret and, as reported in my account of 13th it took the mid upper gunner (whose name was Gunnar Sandvik!) to crawl back along the fuselage to operate the manual release from outside the turret and drag Jimmy from his incarceration. Dad discovered that his parachute stowed under his table had burst open. Amongst all this, Dad sat and continued his job as Navigator calculating a course for Joe to take them out of the immediate area back up the Gironde, before setting off with Freddie to attempt to ditch the bombs hung-up in the bomb bay.

France 18th August 1944.

Its late evening and this is the fifth day Joe has been on the run. He has hidden by day grabbing but a few hours’ sleep in total, too afraid of being discovered to sleep properly. Haystacks, barn lofts and under raised farm buildings have been his preferred hiding places. By night he has moved as fast as he could in a roughly easterly direction inland away from the crash site and the area heavily patrolled by Germans searching for him. He had swum across waterways and run through the forest and surrounding fields but in the virtual darkness he had often become disorientated. He had a small compass hidden in one of his jacket buttons -standard for all the airmen - and his standard issue escape pack which included a cloth map, but it was barely a foot square and of the whole of France so of little use in determining exactly where he was. In the darkness and without a light it was virtually impossible to read anyway, and the compass was too small to be seen also.

[Note by Peter's daughter, Sandra - I still have Dad's silk map]

He had a pounding headache, a gash to the head, bruises and aching all over his body and a high-pitched whistle in his left ear from the engine that had screamed out of control. We know this as tinnitus and it was still with him 50 years later when he gave his account.

He had a persistent raging thirst, only occasionally finding a water barrel or waterway he felt confident enough to drink from, and a chronic hunger. Three days previously, he had been discovered whilst asleep in a haystack by a farmer. Joe was glaringly conspicuous since he was still in uniform. All of the crew flew in full uniform under their flying over-suit but on the hot August day Joe had foregone his over-suit. Before Joe had a chance to say anything the farmer turned and went back to the house. Joe was sure his luck was out and the farmer was contacting the Germans. To his surprise a few minutes later the farmer and his wife re-appeared with a package containing bread and hard-boiled eggs. They indicated to Joe that he must leave immediately and communicated in broken English that, if caught, he must say he stole the food. The farmers were taking a huge risk – if found out they would be shot for assisting the enemy. This had been Joe’s only food since the mandatory bacon and eggs (on August 13th) enjoyed by all Lancaster crews before leaving on a mission.

At about this time, very late evening on the 18th, Joe decided it was fruitless to continue on the run with his injuries, hunger, thirst, and not knowing where he should be going. It was time to make contact with the French and hope they could help and not turn him over to the Germans. He made his way to the road with the intention of doing what had been recommended in evasion training – find a church and contact the priest or parson. As he was passing a haystack he was confronted by a startled young man and his girlfriend. Their surprise soon subsided because Joe had been spotted earlier in the evening by children and the word had quickly gone round that there was a British airman in the countryside. In no time he was in a house having his first meal for far too long. Joe soon realised how bad his French was and regretted not paying more attention in his language lessons at school!

He learned that the couple who found him were Paul and Paulette and that in the morning he would be given a new suit, the one in which Paul was to be married! He was going to be moved to a ‘safe house’.

In the Bordeaux prison Dad and the others had been joined late last night in another cell by some German naval officers who were themselves prisoners. The day before Dad had taken a brief detour through a door at the end of the corridor while the guards were preoccupied to see if he could find an escape route, but to no avail. This door led to an enclosed yard with tall wooden posts set in the ground. Shortly after day break the naval prisoners were led with chains around their ankles and wrists through the door. There were shots and then silence. The prisoners were not seen again. Pat subsequently found out from a guard that some submarine commanders in the very submarine pens they had bombed had refused to take their vessels out because of relentless attacks from the RAF. It was surmised they had been shot for insubordination.

There was clearly disorder setting in amongst the Germans. The allies’ advance through France must be having an effect on German moral and anything could happen to the crew of Lancaster VN-D if their captors became trigger-happy. Dad and Freddie knew as soon as the next opportunity arose, if there was to be a next time, they had to find a way to escape.

Yesterday, Dad, the crew and the Americans were told they were to be moved again. They hadn't been given any breakfast so a row broke out with the guards and they refused to move from the cell and corridors where the 14 of them had started to kick up a fuss in order to cause maximum disruption. While the guards were distracted Dad nipped into their office. When the crew had first been captured they were strip searched and all their personal efects taken. When they were later given back the bag of belongings they all had various items missing. Dad and Joe, as Navigator and Pilot, were issued by the RAF with watches made by Rolex and Omega to give precise time so, for example, when Dad gave Joe a turning point or altitude change for a specific time they both knew their watches were synchronised. Dad was given specific orders to always return the watches after each mission since they were in short supply and very expensive. Dad wanted his watch back and dived into an old wooden desk, rummaging through the draws and amongst papers. There he found not only the watch but a ring and more besides. He returned to the melee in the corridor no doubt pleased he could fulfil his order and return the watch to the RAF should he get home to Blighty.

[Note by Peter's daughter, Sandra-

I remember this watch really well. It was an Omega . He kept it after the war as he felt he had earned it!

He wore it on his left arm with the face on the inside of the wrists. Was this because would be more prone to damage on the outside of the wrist and could be more easily tilted to read in this position when the hands were occupied? He had a distinctive way of tilting his wrist to read the dial. I remember trying it on - it seemed enormous on my little wrist. If you look at the film 'Returning The Empty', you can actually see it!]

Today, they all arrived at a huge Luftwaffe base at Merignac. Now it would seem they possibly were to be flown to Germany, but the allies had made a real mess of the runway with various bombing raids so it wasnt clear to anyone why they were there. They filled out Red Cross forms. This meant they were officially registered as prisoners of war so at least the families would eventually be notified by the Red Cross that they were alive. Lots of questions but only rank, name and serial number declared. Here they were given two new guards, one small and one large. They were ordered by the officer to fix bayonets and guard the door. When the little one stood to attention he was shorter than his rifle, which caused great amusement to the British and Americans alike.

Once the officer had gone, they were allowed to do pretty much as they like. They were in the German Officers' Mess, where there was a piano. Bill Gray could play piano so a sing-song soon broke out including a rendition of a sad German song about a camp follower called Lili Marlene which the guards listened to intently. Dad and Bill both say in their diaries that whenever they heard that tune after the War it took them back to that time.

In a village somewhere to the east of the Foret de la Coubre Joe was kitted out in Paul's new wedding suit. A Frenchman arrived at the house. Joe was to later get to know his name - Monsieur Gildas Gueran. He had two bicycles. Joe was to follow him but at a distance behind in case he was pulled up by the Germans and with the strict understanding that he had stolen the bike and clothes and knew no-one in the area. Joe was now to make a long bike journey guided by a member of the French Resistance through open country roads directly under the noses of the Germans. Bear in mind that since Joe was in civilian clothes with no means of proving he was an RAF pilot and not registered with the Red Cross as a prisoner of war he would almost certainly be considered a spy and shot if caught. The risk to M. Gueran was, of course, potentially even greater since the Germans had been known to shoot all the family members of someone caught collaborating with the enemy as a Resistance worker.Today, they all arrived at a huge Luftwaffe base at Merignac. Now it would seem they possibly were to be flown to Germany, but the allies had made a real mess of the runway with various bombing raids so it wasnt clear to anyone why they were there. They filled out Red Cross forms. This meant they were officially registered as prisoners of war so at least the families would eventually be notified by the Red Cross that they were alive. Lots of questions but only rank, name and serial number declared. Here they were given two new guards, one small and one large. They were ordered by the officer to fix bayonets and guard the door. When the little one stood to attention he was shorter than his rifle, which caused great amusement to the British and Americans alike.

Once the officer had gone, they were allowed to do pretty much as they like. They were in the German Officers' Mess, where there was a piano. Bill Gray could play piano so a sing-song soon broke out including a rendition of a sad German song about a camp follower called Lili Marlene which the guards listened to intently. Dad and Bill both say in their diaries that whenever they heard that tune after the War it took them back to that time.

In a village somewhere to the east of the Foret de la Coubre Joe was kitted out in Paul's new wedding suit. A Frenchman arrived at the house. Joe was to later get to know his name - Monsieur Gildas Gueran. He had two bicycles. Joe was to follow him but at a distance behind in case he was pulled up by the Germans and with the strict understanding that he had stolen the bike and clothes and knew no-one in the area. Joe was now to make a long bike journey guided by a member of the French Resistance through open country roads directly under the noses of the Germans. Bear in mind that since Joe was in civilian clothes with no means of proving he was an RAF pilot and not registered with the Red Cross as a prisoner of war he would almost certainly be considered a spy and shot if caught. The risk to M. Gueran was, of course, potentially even greater since the Germans had been known to shoot all the family members of someone caught collaborating with the enemy as a Resistance worker